What's in a Name?

Make it snappy

Sparks, chippies and drippies. Every profession and trade has its nickname. Most are sort of affectionate, some insulting and a few even respectful. I noticed in a recent issue of Private Eye, which has always had an entertaining inside track into the world of journalism, a small piece revealing a plea from the Guardian’s head of photography Fiona Shields. She has asked her newsdesk colleagues to stop referring to photographers as “snappers”. For Fiona, the term is “demeaning” – it “devalues our visual journalism and is demoralising for the photography team”. I think I agree with Fiona, but it would be interesting to work out why.

The best place to start is the word itself. Snappers is not another word for small crocodiles, but the description of someone who takes ‘snapshots’. The consensus dates that word to the 1800s in the context of hunting with a shotgun. It’s a quick, minimally considered crack at the target with results that can range from the fortuitous (except for the hunted animal) to disastrous (think another member of the shooting party pulling lead pellets out of his backside).

There’s pretty good evidence that the first person to apply it to photography was the all-round scientist and photographic pioneer John Herschel. Probably his most significant contribution to the new medium was his discovery of a method for fixing images. But his contribution to the language of photography is almost as important. In a world of Calotypists and Daguerreotypists he was among the first, in the 1840s, to routinely refer to ‘photographers’ taking ‘photographs’ in a ‘photographic’ way. And, in an article published in the Photographic News in 1860, he pondered the future and wondered if it would offer the possibility of “taking a photograph, as it were, by a snap-shot – of securing a picture in a tenth of a second of time….”

Fast-forward to the end of the nineteenth century and the future has arrived. Exposure times have shrunk from minutes to fractions of seconds and a whole new way of seeing the world has emerged. Photography has become quick, simple and available to all rather than being the almost exclusive preserve of well-heeled amateurs and hard-bitten professionals.

The early 1900s saw the adoption of photography into ordinary domestic life. From Kodak’s Box Brownie to the cartridge-loading instamatic of the 1970s and with every new handy model in between, families had an easy means of recording their lives. Over the decades, ordinary people with no other motive than to make memories have been firing off snapshots by the million. The perfection of portable digital technology has only accelerated the phenomenon, and snapshots are probably better counted in the billions now.

This is the point at which the word ‘snapshot’ takes on all of its colour and embedded significance. Yes, it means a quickly taken photograph, but it implies much more than that. It’s not just about the image itself – clumsy, funny, boring or technically inept – but about the photographer. Used by those who consider themselves Photographers with a capital ‘P’, snappers might seem a derogatory term. It certainly has been used as an insult, but I think it’s a bit more nuanced than that.

Given the ubiquitous nature of photography, it’s inevitable that language has arisen to mark out particular practices and types of image. That line between professional and amateur, for example, is particularly interesting. Technically, this distinction is simply a matter of whether or not the photographer gets paid. But there’s a cachet to being a professional that many amateurs aspire to. It’s no coincidence that photographic gear and supplies aimed at those who are serious about their photography often come with the prefix or suffix ‘pro’ slapped on them.

As in so many areas, the digital revolution has – to mix the metaphors – stirred the pot and blurred the boundaries. If professional status only means getting paid for your pictures, then it is open now to almost anyone with a smart phone. As far back as 2012, one-time Daily Mirror editor Roy Greenslade was accepting the inevitability of an almost total clear-out of newspaper staff photographers and an increasing reliance on ‘citizen journalists’ sending in their snaps of police tape on the high street.

And it would not matter, in this view, that these would be ‘snaps’ – quickly recorded images of the unfolding scene taken by passers-by with no training in or instinct for the medium. Photographs supplied by people with no interest in photography who would just be happy to find fifty quid or so popping into their bank account. Many in the industry (the Professionals) feared a dramatic decline in the look of local and national newspapers. They also, understandably, worried that their livelihoods would be taken from them.

Thankfully, to a large extent, concerns about a reduction in the quality of images appearing in the press have proved unfounded. And that’s largely down to the work of experienced picture editors like Fiona Shields. Smart phone, CCTV and dashcam snaps of dramatic news events supplied by witnesses increasingly have their place in news coverage. But the identity of a newspaper often lies in the photography now provided by teams of professional freelancers to cover editorial and analytical pieces, staged events and sports.

The edict against the word ‘snappers’ is an attempt to maintain respect for this work and those who create it. It may seem a little over-sensitive and defensive, but the professional pride of photographers faces more immediate threats than that of carpenters or electricians. No one would seriously believe that anyone could pick up a handsaw and do what a chippie does, or that handing someone a volt meter will turn them into a spark. On the other hand, give anyone a camera and show them where the button is…

So, the question remains: is there a more respectful (but amusing) nickname that could be used for professional newspaper photographers? One that would distinguish them from the great mass of snappers out there – a name with a maximum of two syllables that would not carry a perceivable insult to their craft?

History Corner

Holy Cow!

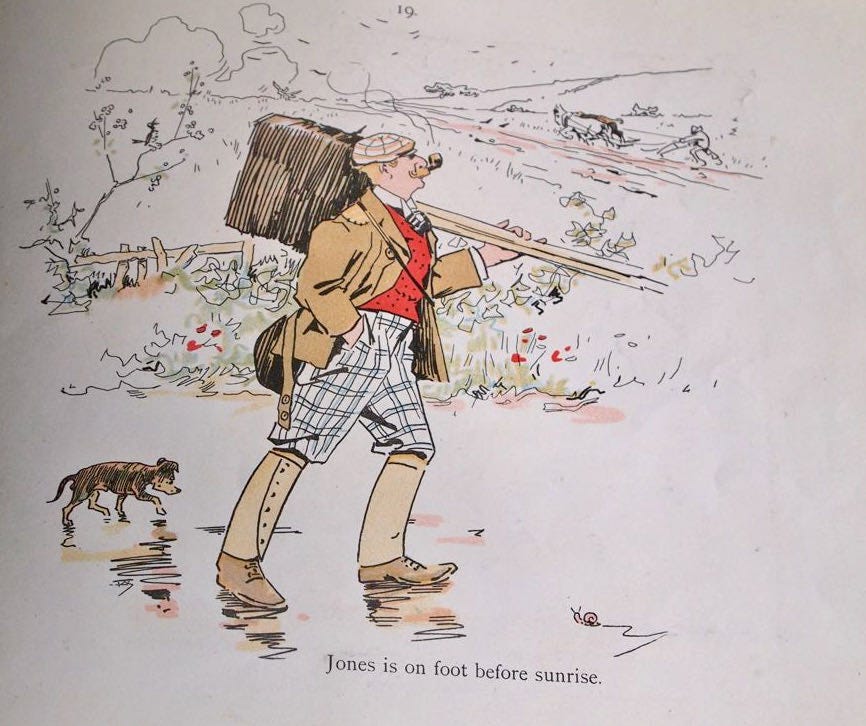

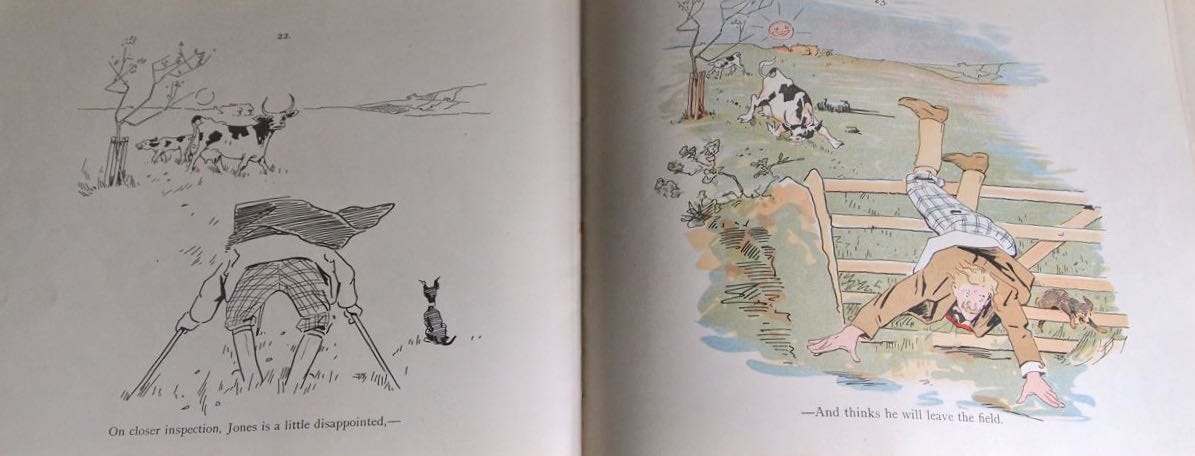

When Kodak opened up photography to the masses with their box cameras and the promise of simplicity announced in the slogan ‘You Press the Button, We do the Rest’, they put down a marker for the absolute democratisation of the medium. One effect of that was to give rise to the idea of the ‘serious amateur’. Anyone who owned a Brownie could be called an amateur, and there were photographic clubs and loose groups who specialised in what became known as ‘hand cameras’. But to be a real devotee of the lens was to continue to lug around a large plate camera on a tripod.

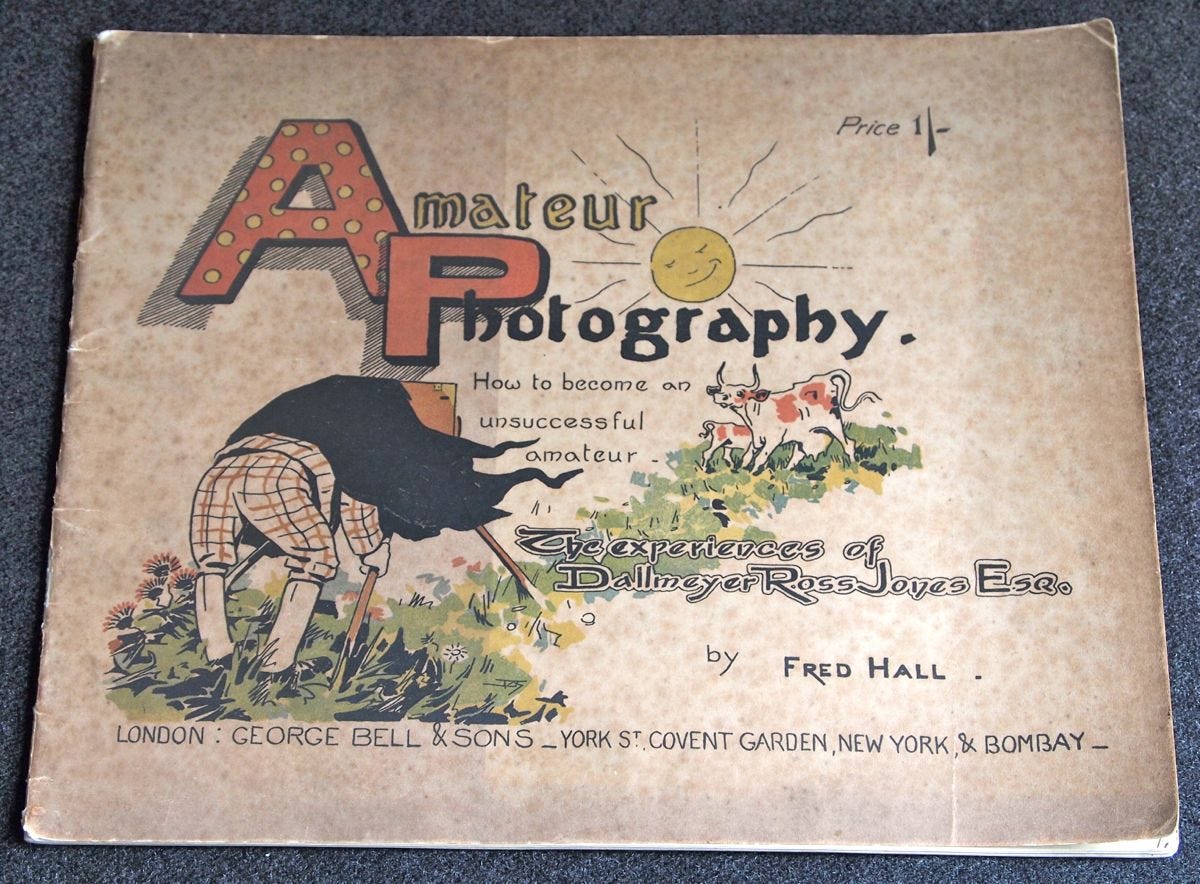

All the paraphernalia of photography and the arcane mysteries that lay beneath the dark cloth were a rich source of amusement to the man on the Clapham Omnibus. This book from 1880 was illustrated by Fred Hall, a Newlyn Group artist who enjoyed a sideline in caricature.

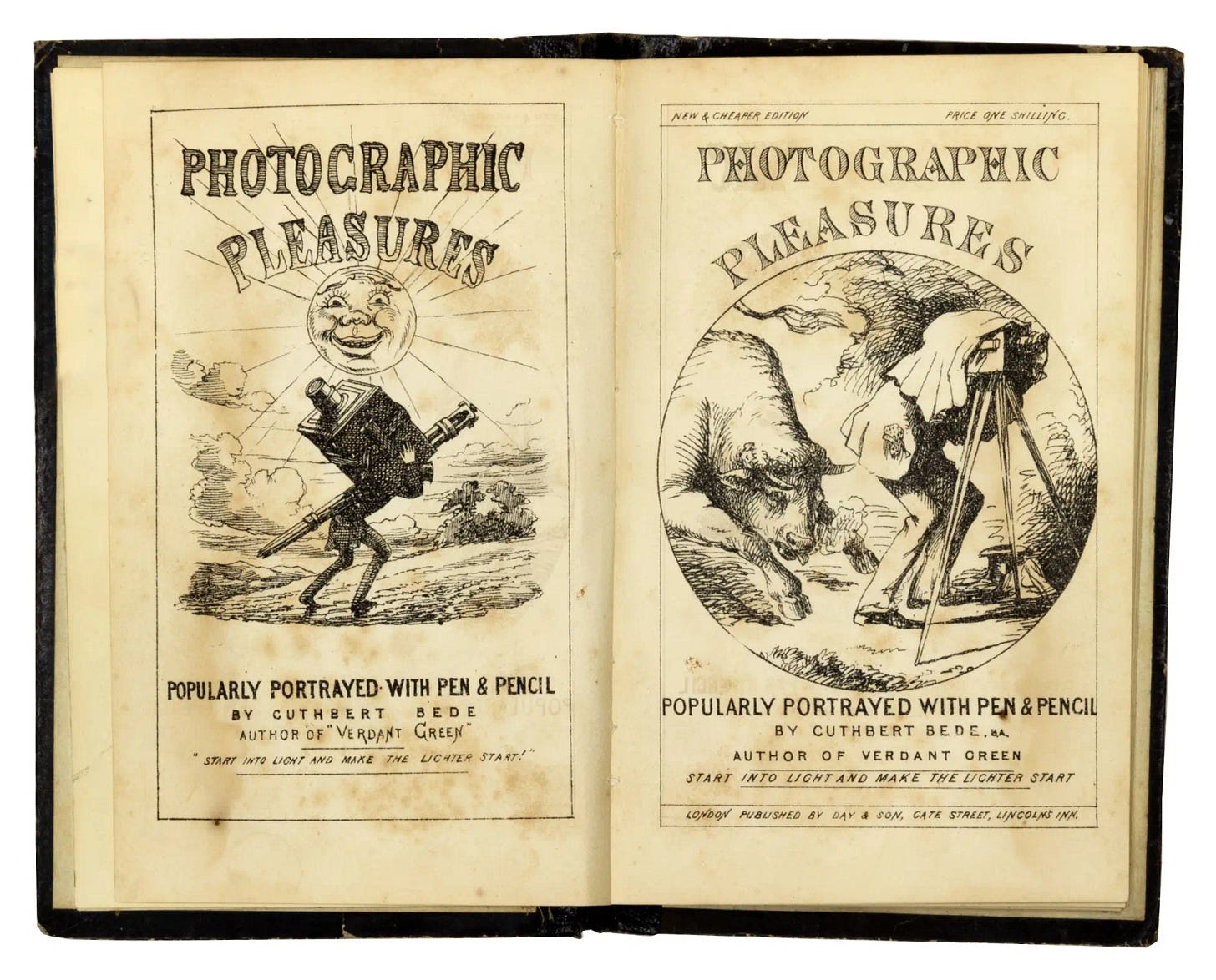

His fun-poking was in a fine tradition that included sketches by artists including John Leech and Honoré Daumier. But perhaps the first to laugh at those crazy photographers was Cuthbert Bede whose 1855 book Photographic Pleasures contains some of the earliest cartoons on the subject. Fred Hall was obviously aware of this work and what is striking is how little the hilarious equipment (the chemistry was a different matter) or the jokes changed over the 25 years.

And finally, this is what The Critic had to say in April 1902 about a lovely cow picture sent in by Narcissus…

“Narcissus - Here is a golden opportunity lost. Could there have been anything nicer and more desirable than the materials at hand? A daisy-dotted meadow surrounded by fine trees, some nice cattle and a charming little girl with a milking pail. And yet Narcissus has made a frizzle of it. Looked at as a whole, the thing is too spotty. The daisies, for instance, create little annoying points of light and appear to be an encumbrance rather than a pictorial gain. The background also is extremely full of detail due to the use of a small stop, and consequently the cattle do not stand out as they should. Then, towards the left-hand side there is a great unoccupied space which is a terrible eyesore. … Suppose she had made sure that the sun shone from a little behind the camera, then suppose she had used a larger stop and focussed only on the cows, which would have made a reduction of detail in the distance, and lastly, suppose she had waited until the animals and the little girl fell into one of the approved artistic shapes, a pyramid or something of that sort.”

Thanks for reading.

Fantastic. Really enjoyed these reflections on the nuanced language of photography. The phrase “snapshot aesthetic” is interesting in this context, a style of image-making that is often very intentional. The thing I love most about photography is its indeterminacy and contradictions. Endlessly fascinating and increasingly weird the more one knows about it.