Life Line

An actor's life in pictures

I’d like to start this post with Terence Stamp. The British actor died this week and The Guardian looked back at his life with a series of photographs.

All of us live our lives more or less under the eye of the camera. But for actors, from celebrity to jobbing extra, it’s a professional requirement. As a consequence, this set of chronological images is more the record of a career than a life. It may be that there are photos of the actor bleary in a pub or red-eyed in a conical party hat, but those are for friends, family and the cradle-to-grave biography. These images are as much about the outlets and photographers as they are about Terence Stamp.

Picture editor Greg Whitmore has done a decent job of tracing Stamp’s path. He’s helped by the fact that the subject has one of those faces whose features are fixed like a mask, particularly the set of his mouth. That tight, not-quite-pursed expression is there in all of the images from first to last and could be regarded as Terence Stamp’s brand. It’s even there in the supposedly spontaneous picture of him playing a board game with his siblings while the doting parents look on, and in the paparazzi snap of him in the Bag O’Nails club in Soho.

While photographers to the stars have always been the alchemists creating and maintaining the public face, it’s curious that the magic often comes about because of an off-camera relationship; through a private understanding the photographer has of the subject behind the billboard or the magazine page. Photographer Sam Shaw, for example, was a close friend and confidant of Marylin Monroe as well as being a key reason why the world sees her as it does. Terence Stamp, along with his friend Michael Caine, was a fixture in the swinging London of the 1960s. Both were included in David Bailey’s era-defining Box of Pin-ups in 1964. Bailey, along with those other beasts of 1960s photography – Terry Donovan, Duffy and Terry O’Neill – knew and mixed with many of the celebrities they immortalised in the world beyond their studio walls.

As a result, these photographers’ images have a curious blend of the formal and the intimate. Bailey, in particular, set the style with close-cropped faces against glimpses of a clean white background. It was a highly effective technique – a process that everyone from Andy Warhol to the Kray Twins was willing to put themselves through in order to stake their place in the pantheon. And it was a style that was imitated and echoed. Terry O’Neill’s double portrait of Jean Shrimpton and Terence Stamp that Whitmore uses here, for example, could easily be mistaken for a Bailey.

Stamp was perfect for Baily’s box. In the publicity still from the creepy 1965 film The Collector, Stamp is shown cradling a Hasselblad in a way he may well have learned from Bailey. In the film, Stamp is a psychopathic bug collector and it’s not too much of a stretch to see the faces in the Box of Pin-ups as specimens fresh from the net. Even the name evokes chloroformed finds skewered to boards and placed under glass.

And yet, across the span of this picture obituary, there is a strong impression of the man’s character. The photographs draw him as self-contained and a little impenetrable. To my eyes, there are only two images here that seem to break the ice at all. One is a 1968 photo of Stamp and his brother outside a Malibu courthouse after their arrest for possession of marijuana, where he sports a wry grin. The other is in an image from the 1967 Ken Loach film Poor Cow – but he was just acting in that.

History Corner

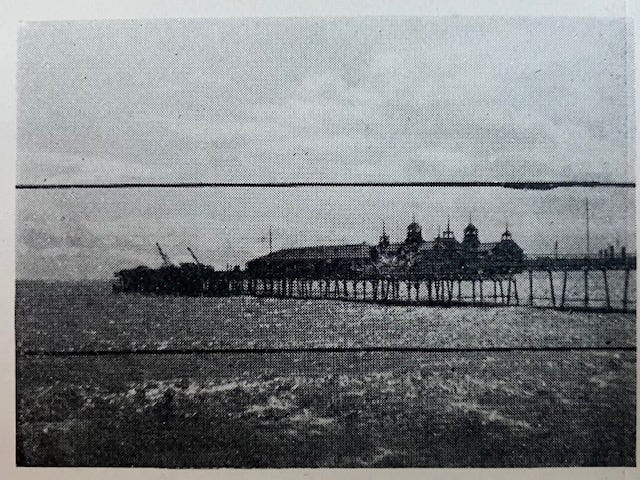

As the summer holidays enter their final couple of weeks and holidaymakers prepare to pack away their buckets and their spades, here’s what The Critic in the December 1901 issue of Practical and Junior Photographer had to say about a reader’s attempt to photograph a seaside pier…

“HECTOR - We publish this as an example of what not to do, and yet what is constantly being done. There could be nothing more abominable than a pleasure pier at low tide (unless, perhaps, it is the same pier at high tide), especially when taken on the ordinary plate, which on account of its squareness means that the pier, if any fair quantity of it is included, comes out as a narrow strip in the midst of a waste of cloud and sand. … The only way out of the matter if a pier must be photographed, is to make a long, narrow picture of it, waiting, if possible until the sun is directly behind it and partly hidden in clouds, so as to get a silhouette night effect. This being done, the trimming knife must be used until practically only the portions we indicate are retained, then the best is made of a bad job. Our advice, however, is to leave these company-promoted structures alone, and go in for Nature pure and simple.”

It’s interesting to think that those wonderful seaside structures that we mostly now cherish and protect were considered vulgar commercial intrusions by some people much closer to the time when they were built. Also, that tip about waiting for the sun to get partially obscured by cloud to give a silhouetting effect is the basis of the technique used by early black and white film makers to give the impression of night time in the days before more sensitive film stock - Day for Night, as it was known.

Thanks for reading.